Newsletter

The No. 2576 Spanish Arm Chair, the latest addition to the TRRF collection, convincingly demonstrates Gustav Stickley’s ability to create assured designs right from the start of his Arts and Crafts venture. Functional and harmoniously ornamented, the chair’s crisp, straightforward form anticipates the best Craftsman furniture work, but it also acknowledges both a recent and a more distant past.

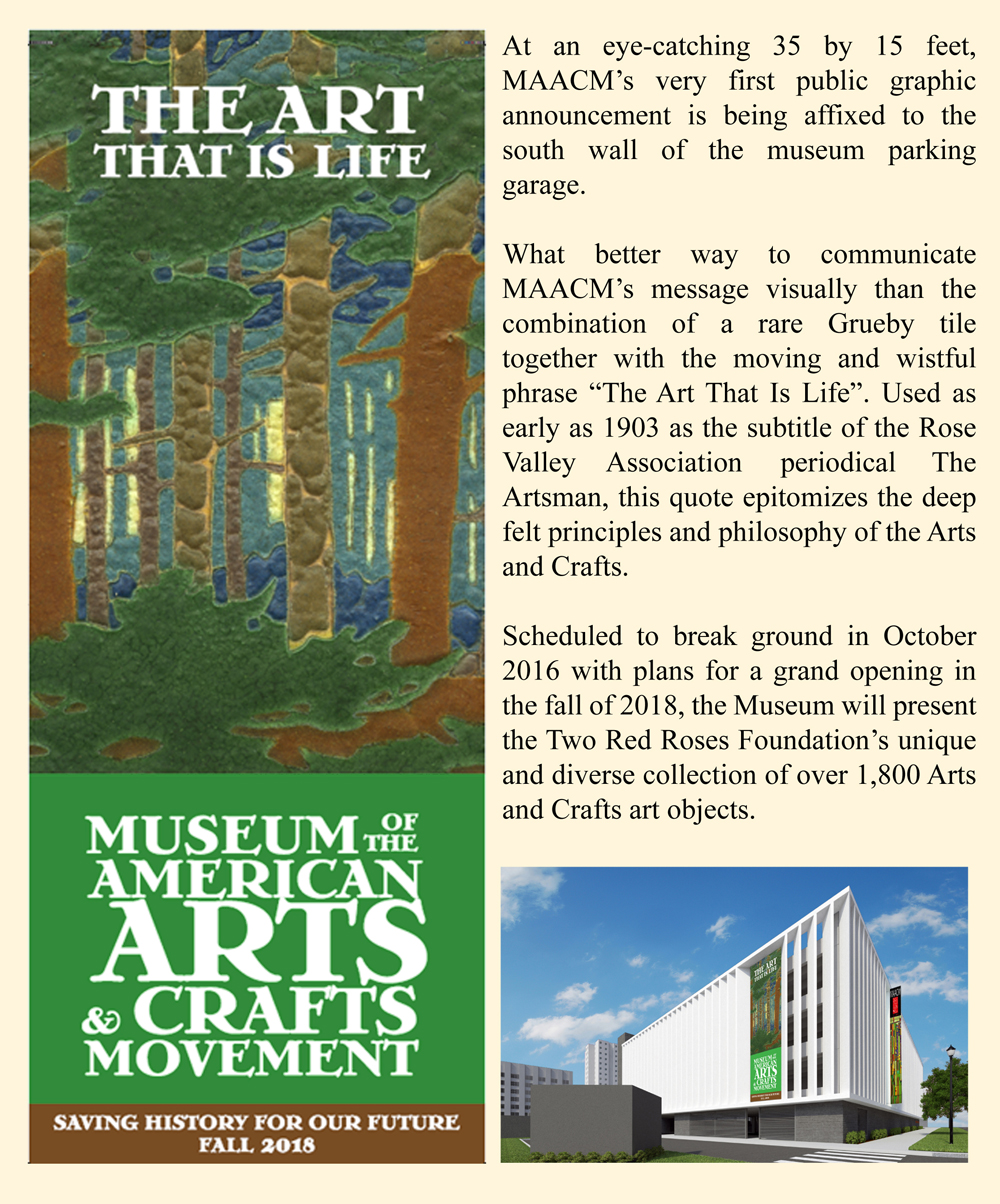

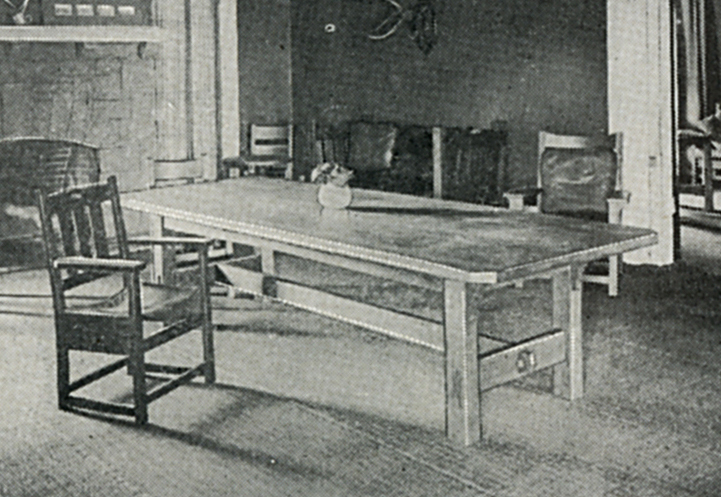

Interior view of the Onondaga Golf Club in Syracuse, NY, with a No. 2576 Spanish Arm Chair prominently in view. The Craftsman 1 (October 1901), plate following p. iv. TRRF Collection

It was in production only briefly -- perhaps about a year. Illustrated in Stickley’s 1900 catalogue, and catalogued again in early 1901, it was offered in oak for $13.75 – the TRRF example is oak -- and mahogany for $17.00. It is not in the firm’s June 1901 catalogue, evidently no longer being made. An example, however, can be seen in an interior view of the Onondaga Golf Club, in Syracuse, published in the first issue of The Craftsman magazine, in October 1901.

Though made for use and comfort, the chair is innately decorative. This is partly due to the distinctive shape of its legs and stretchers: they are rectangular in section, in contrast to the square-sectioned planks common to most Stickley chairs. Thus constructed, the firm’s chairs generally imparted a sense of strength achieved with mass; the Spanish Arm Chair’s visibly lighter members, however, draw attention to form and volume, suggesting not mass but tensile strength.

Stickley’s earliest promotional text stressed that chairs meant for a living room should be readily moveable, and the comparatively thin rails and stiles and un-upholstered leather seat contribute to this model’s evident mobility. The sawn-out "handhold" in the top rail similarly expresses this theme: its shape and size makes the chair easy to pick up and move. But is equally true that this rounded cutout is ornamental, a focal point that emphasizes the chair’s apparent lightness. This open, slightly curving, and modest shape creates a dramatic contrast to the straight structure and dark wood. Stickley often embellished his 1900 furniture with sawn-out elements, and the "handhold" that punctuates this chair’s top rail typifies that decorative method: such sawn ornament required only standard wood-working techniques and adhered to Arts and Crafts notions of simplicity. It was a cost-effective way to enrich his firm’s plain, refined designs.

Although the chair’s three vertical back slats are necessary structural and functional components, they also exemplify the understated ornament that Stickley favored. Back slats of his firm’s chairs were most often cut straight, but on this model they almost imperceptibly curve inward at the point where they join the back’s lower rail. These subtle curves seem to allude to – even point toward – the tenon ends hidden within the horizontal rail: Stickley here emphasizes structure without literally revealing it.

16th Century Spanish chair with slung leather seat, from H.D. Eberlein and A. McClure, “Spanish Tables and Seating Furniture of the 16th and 17th Centuries,” House & Garden Vol. 33 (Feb. 1918), p. 39. TRRF Library

The seat is simply made. No more than a wide piece of leather draped between the seat rails, its construction can be seen as rudimentary, one inevitable way to conceive a seat. It almost seems to float above the rectangular voids defined by the stretchers that brace the legs. Its catenary curve restates – on a larger scale – the curved lines of the "handhold" and the shaped back slats directly above, further unifying the design and adding another curve that contrasts with the chair’s more apparent rectilinearity. The pliant, textured leather gives this chair its name, at least in part. Early Stickley catalogues routinely praised the "incomparable" leatherworkers of medieval Spain, and made the claim that the firm used traditional methods to produce richly hued leathers rivaling "the old Cordovan products." The straight rows of large, round-headed nails that fasten the leather to the chair frame add decorative geometric pattern, and their patinated, light-catching surfaces articulate the most visually compelling aspect of this entire design -- the deep, dramatically overstated seat rails. This model is possibly attributable to the Stickley designer LaMont Warner. Its draped leather seat, emphatic flanks, and large, reflective nail heads seem drawn from an armchair designed by the English architect M. H. Baillie Scott and published in International Studio in August 1898. Warner’s extant files include illustrations clipped from that article. An appealing assemblage of mostly period motifs, the Baillie Scott chair is traditional; in contrast, Stickley’s pared-down Spanish Arm Chair is “modern,” in the sense that it is essentially free of retrospective elements. But both are visibly indebted to 16th century Spanish armchairs similarly made with slung leather seats. This heritage may suggest another reason why Stickley gave his No. 2576 chair its evocative "Spanish" name.

-David M. Cathers, 2016

MAACM Raises Its First Banner